United States - Taxation of cross-border mergers and acquisitions

Taxation of cross-border mergers and acquisitions for United States.

Taxation of cross-border mergers and acquisitions for United States.

Introduction

United States (US) tax law regarding mergers and acquisitions (M&A) is extensive and complex. Guidance for applying the provisions of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended (Code), is generally provided by the US Treasury Department (Treasury) and Internal Revenue Service (IRS) by means of Treasury Department regulations, revenue rulings, revenue procedures, private letter rulings, announcements and notices. The courts and the relevant legislative histories provide further interpretation of the tax law and relevant guidance.

Parties may structure a transaction in a non-taxable, partially taxable or fully taxable form. In structuring a transaction, the types of entities involved in the transaction generally help determine the tax implications.[1]

A non-taxable corporate transaction generally allows the acquiring corporation to take a carryover basis in the assets of the target entity. In certain instances, a partially taxable transaction allows the acquiring corporation to take a partial basis step-up in the assets acquired, rather than a carryover basis. A taxable asset or share purchase provides a basis step-up in all the assets or shares acquired. Certain elections made for share purchases allow the taxpayer to treat a share purchase as an asset purchase and take a basis step-up in the acquired corporation’s assets.

Taxpayers generally are bound by the legal form they choose for the transaction. The particular legal structure selected by the taxpayer has substantive tax implications. Further, the IRS can challenge the tax characterization of the transaction on the basis that it does not clearly reflect the substance of the transaction.

Recent developments

This section summarizes US tax developments that occurred from 1 February 2018 to 1 January 2021. To stay up-to-date on the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (the ‘2017 Tax Law’ – TCJA), refer to the KPMG US external website dedicated to the 2017 Tax Law. To stay up-to-date on US COVID-19-related tax legislation, refer to the KPMG US COVID-19: Insights on tax impacts external website. Please note that due to a new Congress and Administration under President Joe Biden as of January 2021, more US tax policy changes may be forthcoming. To stay up-to-date on US tax legislation, refer to the KPMG US TaxNewsFlash website.

The 2017 Tax Law

The 2017 Tax Law, enacted in December 2017, significantly affected US cross-border taxation. This legislation is the most extensive rewrite of the US federal tax laws since the Tax Reform Act of 1986. The 2017 Tax Law, which affected both common US inbound and outbound structures, has a significant impact on many foreign buyers of US companies.

For corporations, the centerpiece of the 2017 Tax Law is the permanent reduction in the corporate income tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent, which generally took effect on 1 January 2018.

The 2017 Tax Law is highly complex in that it layers new law over years of existing US federal tax law as well as eliminates and modifies various sections of existing tax law. The US Treasury and the IRS have been engaged in a lengthy and time-consuming process of drafting interpretative regulations and guidance that address the legislation’s provisions. Additionally, there has been discussion as to whether the US Congress will enact a ‘technical corrections’ bill that makes retroactive changes to the 2017 Tax Law; prospects remain uncertain.

The 2017 Tax Law fundamentally changed the taxation of US multinational corporations and their foreign subsidiaries. US multinational corporations under the old law were subject to immediate and full US income taxation on all income from sources within and without the US. The earnings of foreign subsidiaries under the old law, however, generally were not subject to US income tax until the earnings were repatriated through dividend distributions (although under an anti-deferral regime (subpart F), which dated back to 1962, certain categories of foreign subsidiary earnings were taxed in the hands of the US corporate owners as if such amounts had been repatriated via dividend distribution).

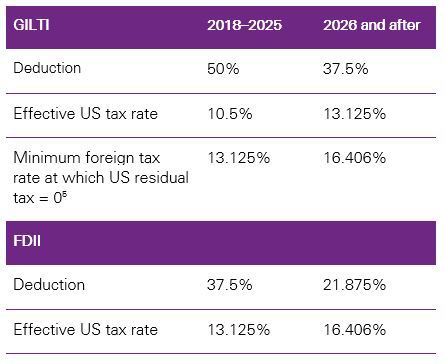

By contrast, the earnings of foreign subsidiaries under the 2017 Tax Law are either subject to immediate taxation under expanded anti-deferral provisions or are permanently exempt from US taxation. The 2017 Tax Law generally retains the existing subpart F regime that applies to passive income and related-party sales and services income, and it creates a new, broad class of income (‘global intangible low-taxed income’ — GILTI) that is also deemed repatriated in the year earned and, thus, is also subject to immediate taxation. While GILTI is effectively taxed at a reduced rate, subpart F income is subject to tax at the full US rate.

To accomplish this shift to the new regime, the new law included several key features, including:

- a 100 percent deduction for dividends received from 10 percent-owned foreign corporations

- a tax on GILTI

- a one-time transition tax or deemed repatriation tax on the accumulated earnings of certain foreign corporations.

Some of the stated goals in enacting the 2017 Tax Law were simplification and a shift from a worldwide system of taxation to a territorial tax system (i.e. a tax system that taxes profits where they are earned). Whether the 2017 Tax Law achieves these goals is debatable. The 2017 Tax Law contains complex new provisions that require significant reasoned analysis and judgment, as well as additional administrative guidance to properly implement. While it might be nominally accurate to state that the new tax system moves towards a territorial system — because certain profits earned by foreign subsidiaries are not subject to immediate taxation and will not be taxed when repatriated — the non-taxable profits are (in most situations) a small portion of the profit pool. Moreover, by expanding the anti-deferral regime to include GILTI (albeit at a reduced effective rate), the 2017 Tax Law expands the base of cross-border income that is subject to immediate US income taxation.

Other key provisions of the 2017 Tax Law are a reduced tax rate for a new class of income earned directly by US corporations (‘foreign-derived intangibles income’ — FDII) and a new tax (the ‘base erosion and anti-abuse tax’ — BEAT) on deductible payments made by US corporations to related foreign persons.

Various provisions of the 2017 Tax Law are discussed in further detail throughout this report. As a general matter, it is important to keep in mind that many of the 2017 Tax Law’s provisions affect foreign buyers of US targets and, more generally, foreign multinationals that have significant US operations. In practice, some of the provisions will operate to increase US taxable income when applicable. Due to the significant changes, consideration of the 2017 Tax Law is especially important when completing tax due diligence reviews, defining tax indemnities, and undertaking acquisition integration planning. From a tax due diligence perspective, areas of key focus from the 2017 Tax Law perspective include, for example, consideration of:

- whether the US target has properly calculated its mandatory repatriation tax (if applicable)

- whether the US target has any structures or transaction flows in place that would give rise to US tax exposures, for example, under the BEAT regime and/or the new hybrid mismatch rule

- whether the US target is highly leveraged

- whether the US target has any intellectual property (IP) planning structures in place.

For those foreign companies with significant US operations that did not plan accordingly (e.g. through supply chain restructuring), the collective application of certain provisions of the 2017 Tax Law could have resulted in an unfavorable impact on a foreign company’s global effective tax rate despite the US corporate tax rate reduction.

Asset purchase or share purchase

The decision to acquire assets or stock is relevant in evaluating the potential tax exposures that a buyer may inherit from a target corporation. A buyer of assets generally does not inherit the US tax exposures of the target, except for certain successor liability for state and local tax purposes and certain state franchise taxes. Also, an acquisition of assets constituting a trade or business may result in amortizable goodwill for US tax purposes. However, there may be adverse tax consequences for the seller in an asset acquisition (e.g. depreciation recapture and double taxation resulting from the sale followed by distribution of the proceeds to foreign shareholders).

By contrast, in a stock acquisition, the target’s historical liabilities, including liabilities for unpaid US taxes, generally remain with the target (effectively decreasing the value of the buyer’s investment in the target’s shares). In negotiated acquisitions, it is usual and recommended that the seller allow the buyer to perform a due diligence review, which, at a minimum, should include review of:

- the adequacy of tax provisions/reserves in the accounts, identifying open years and pending income tax examinations

- the major differences in the pre-acquisition book and tax balance sheets

- the existence of special tax attributes (e.g. ‘net operating loss’ — NOL), how those attributes were generated and whether there are any restrictions on their use

- issues relating to acquisition and post-acquisition tax planning.

Under US federal tax principles, the acquisition of assets or stock of a target may be structured such that gain or loss is not recognized in the exchange (tax-free reorganization). Such transactions allow the corporate structures to be rearranged from simple recapitalizations and contributions to complex mergers, acquisitions and consolidations.

Typically, a tax-free reorganization requires a substantial portion of the overall acquisition consideration to be in the form of stock of the acquiring corporation or a corporation that controls the acquiring corporation. However, for acquisitive asset reorganizations between corporations under common control, cash and/or other non-stock consideration may be used.

There may be restrictions on the disposal of stock received in a tax-free reorganization. The buyer generally inherits the tax basis and holding period of the target’s assets, as well as the target’s tax attributes. However, where certain built-in loss assets are imported into the US, the tax basis of such assets may be reduced to their fair market value.

In taxable transactions, the buyer generally receives a cost basis in the assets or stock. Thus, the buyer may obtain higher depreciation deductions if the acquired item is an asset with a built-in gain, or immediate expensing for certain tangible assets under the 2017 Tax Law for taxable asset acquisitions.

In certain types of taxable stock acquisitions, the buyer may elect to treat the stock purchase as a purchase of the assets (section 338 election discussed later — see ‘Purchase of shares’ section).

Generally, US states and local municipalities respect the federal tax law’s characterization of a transaction as a taxable or tax-free exchange.

Careful consideration must be given to cross-border acquisitions of stock or assets of a US target. Certain acquisitions may result in adverse tax consequences under the corporate inversion rules. Depending on the amount of shares of the foreign acquiring corporation issued to the US target shareholders, the foreign acquiring corporation may be treated as a US corporation for all US federal income tax purposes. In some cases, the US target may lose the ability to reduce any gain related to an inversion transaction by the US target’s tax attributes (e.g. NOLs and ‘foreign tax credits’ — FTCs).

Purchase of assets

In a taxable asset acquisition, the purchased assets have a new cost basis for the buyer (if not immediately expensed under the 2017 Tax Law). The seller recognizes gain (either capital or ordinary) on the amount that the purchase price exceeds its tax basis in the assets. An asset purchase generally provides the buyer with the opportunity to select the desired assets, leaving unwanted assets behind. While a section 338 election (described later) is treated as an asset purchase, it does not necessarily allow for the selective purchase of the target’s assets or avoidance of its liabilities.

An asset purchase may be recommended where a target has potential liabilities and/or such transaction structure helps facilitate the establishment of a tax-efficient structure post-acquisition. For example, under certain conditions, a tax basis step-up resulting from a transaction treated as an asset purchase can help mitigate exposure to the so-called GILTI tax on a go-forward basis. For a discussion of GILTI, see ‘Integration planning for US target-owned intellectual property’ section.

Purchase price

In a taxable acquisition of assets that constitute a trade or business, the buyer and seller are required to allocate the purchase price among the purchased assets using a residual approach among seven asset classes described in the regulations. The buyer and seller are bound by any agreed allocation of purchase price among the assets.

Contemporaneous third-party appraisals relating to asset values can be beneficial.

Depreciation and amortization

The purchase price allocated to fixed assets and to certain intangible assets provides future tax deductions in the form of depreciation or amortization.

As stated earlier, in an asset acquisition, the buyer receives a cost basis in the assets acquired for tax purposes. Frequently, this results in a step-up in the depreciable basis of the assets but could result in a step-down in basis where the asset’s fair market value is less than the seller’s tax basis.

Most tangible assets are depreciated over tax lives ranging from 3 to 10 years under accelerated tax depreciation methods, thus resulting in enhanced tax deductions.

Buildings are depreciable using a straight-line depreciation method generally over 39 years (27.5 years for residential buildings). Other assets, including depreciable land improvements and many non-building structures, may be assigned a recovery period of 15 to 25 years, with a less accelerated depreciation method.

In certain instances, section 179 allows taxpayers to elect to treat as a current expense the acquired cost of tangible property and computer software used in the active conduct of a trade or business. Under the 2017 Tax Law, the deductible section 179 expense limitation is generally 1 million US dollars (US$. This limitation, which is adjusted annually for inflation, is reduced dollar-for-dollar to the extent the total cost of section 179 property placed in service during the year exceeds USD2.5 million (this limitation is also adjusted annually for inflation).

Separately from section 179, so-called ‘qualified property’ used in a taxpayer’s trade or business or for the production of income may be subject to an additional depreciation deduction (‘bonus depreciation’) in the first year the property is placed into service. The 2017 Tax Law expands bonus depreciation to include a 100 percent deduction for the cost of qualified property (generally software and tangible depreciable property with a depreciation life of 20 years or less) that is either original use property or acquired by purchase from unrelated persons. Such property must be acquired and placed in service after 27 September 2017 and before 1 January 2023. The 2017 Tax Law includes a 20 percent incremental phase-down of the ‘bonus’ depreciation percentage for property acquired after 2022, generally allowing businesses to expense 80 percent, 60 percent, 40 percent and 20 percent of the cost of property placed in service in 2023, 2024, 2025 and 2026, respectively. Under the 2017 Tax Law, bonus depreciation is completely phased out in 2027.

Unlike under prior law, the 2017 Tax Law does not limit bonus appreciation to ‘original use property’ that begins with the taxpayer. Specifically, under the 2017 Tax Law, both original-use and used tangible property that is ‘new’ to the taxpayer qualifies for bonus depreciation if certain conditions are met. In general, property is ‘new’ to a taxpayer if the taxpayer and its predecessor did not have a depreciable interest in the property within a look-back period of 5 years. This change governing immediate expensing provides an incentive for foreign buyers of asset-intensive US companies (e.g. manufacturing businesses) to structure business acquisitions as asset purchases or deemed asset purchases (e.g. section 338 elections) instead of stock purchases in those cases where the US target has significant assets that would qualify for 100 percent expensing. When applicable, the 100 percent bonus depreciation rule provides buyers of qualifying US assets with the opportunity to essentially deduct a portion of the purchase price allocable to qualifying tangible property.

Due to the enhanced bonus depreciation provision, it is also anticipated that a seller of a US target company may be more willing to sell assets than before due to the US corporate tax rate reduction and 100 percent expensing for qualifying purchases of depreciable tangible property. Under the 2017 Tax Law, a C corporation that sells an asset and reinvests the proceeds into qualifying depreciable tangible property receives a cash tax benefit due to acceleration of deductions. Specifically, under the 2017 Tax Law, the net effect is a 21 percent tax on the gain realized on the sale, and a 21 percent deduction for the reinvested proceeds if the property qualifies for 100 percent expensing.

Bonus depreciation automatically applies to qualified property, unless a taxpayer elects to forego bonus depreciation in whole or with respect to certain asset recovery classes. Where this election is made, the taxpayer depreciates assets subject to the election under the normal depreciation rules, including accelerated depreciation, if applicable. Taxpayers that wish to further reduce depreciation deductions may elect to use the ‘alternative depreciation system’ under which assets are depreciated using the straight-line method over a longer recovery period. The taxpayer may also elect to use the straight-line depreciation method to determine the adjusted basis of the taxpayer’s qualified business asset investment for FDII and GILTI purposes only, without causing the taxpayer’s property to be ineligible for bonus depreciation for US federal taxable income purposes.

On the other hand, bonus depreciation may not always yield the best results due to potential interactions with other tax provisions. For example, in some situations bonus depreciation might cause a very large NOL, which may offset only 80 percent of taxable income in future years after 1 January 2021, or claiming bonus depreciation deductions in an acquisition year may preclude or limit the deductibility of interest (with respect to tax years after 1 January 2022), GILTI and charitable contributions for the year. Therefore, under certain circumstances, it may be preferable to elect out of bonus depreciation for one or all classes of property.

Where both the section 179 expense and bonus depreciation are claimed for the same asset, the asset basis must first be reduced by the section 179 expense before applying the bonus depreciation rules.

Land is not depreciable for tax purposes. Also, accelerated depreciation, the section 179 deduction and bonus depreciation are unavailable for most assets considered predominantly used outside the US.

Generally, the capitalized cost of most acquired intangibles, including goodwill, going-concern value and non-compete covenants, are amortizable over 15 years. A narrow exception — the so-called ‘anti-churning rules’ — exists for certain intangibles that were not amortizable prior to 10 August 1993, where they were held, used or acquired by the buyer (or related person) before such date or if acquired by an unrelated party but the user of the intangible did not change.

Under the residual method of purchase price allocation, any premium paid that exceeds the aggregate fair market value of the acquired assets generally is characterized as an additional amount of goodwill and is eligible for the 15-year amortization.

Costs incurred in acquiring assets — tangible or intangible — are typically added to the purchase price and considered part of their basis, and they are depreciated or amortized along with the acquired asset. A taxpayer that produces or otherwise self-constructs tangible property may also need to allocate a portion of its indirect costs of production to basis; this can include interest expense incurred during the production period.

Tax attributes

The seller’s NOLs, capital losses, tax credits, disallowed business interest expense and other tax attributes are not transferred to the buyer in a taxable asset acquisition. In certain circumstances where the target has substantial tax attributes, it may be beneficial to structure the transaction as a sale of its assets so that any gain recognized may be offset by the target’s tax attributes. Such a structure may also reduce the potential tax for the target’s stockholder(s) on a sale of its shares when accompanied by a section 338 or 336(e) election to treat a stock purchase as a purchase of its assets for tax purposes (assuming the transaction meets the requirements for such elections; see ‘Purchase of shares’ section).

Value Added Tax

The US does not have a Value Added Tax (VAT). Certain state and local jurisdictions impose sales and use taxes, gross receipts taxes, and/or other transfer taxes.

Transfer taxes

The US does not impose stamp duty taxes at the federal level on transfers of intangible assets, including stock, partnership interests and membership interests in limited liability companies (LLCs). The US does not impose sales/use tax on transfers of tangible assets nor does it impose real estate transfer tax on transfers of real property at the federal level.

Forty-five states, the District of Columbia, and hundreds of localities impose sales/use tax on transfers of tangible personal property for consideration. However, exemptions from sales/use tax may apply to transfers of tangible personal property. For example, many states adopt an exemption from sales/use tax applicable to casual, isolated or occasional sales of tangible business assets. Moreover, exemptions from sales/use tax applicable to machinery and equipment used in manufacturing or sales of inventory (sale for resale) may apply to the transaction.

Most states and/or localities impose real estate transfer tax (RETT) on direct transfers of a possessory interests in real property, including real estate held in fee simple and certain leasehold interests. Some states or localities impose RETT on the transfer of intangible assets, such as stock, partnership interests and LLC membership interests. However, some of these state/localities require the entity meet certain qualifications before imposing RETT, such as qualifying as a defined ‘real estate company’ in a particular jurisdiction.

Purchase of shares

As stated earlier, in a stock acquisition, the target’s historical tax liabilities remain with the target, which affects the value of the buyer’s investment in target stock. In addition, the target’s tax basis in its assets generally remains unchanged. The target continues to depreciate and amortize its assets over their remaining lives using the methods it previously used. Although the target retains its tax attributes in a stock acquisition, its use of its NOLs and other favorable tax attributes may be limited where it experiences what is referred to as an ‘ownership change’ (see ‘Tax losses and other attributes’ section).

Additionally, many of the costs incurred by the buyer and the target in connection with the stock acquisition generally cannot be deducted (but are capitalized into the basis of the shares acquired).

In a taxable purchase of the target stock, an election can be made to treat the purchase of stock as a purchase of the target’s assets, provided certain requirements are satisfied. The buyer, if eligible, can make either a unilateral election under section 338(g) (338(g) election) or, if available, a joint election (with the common parent of the consolidated group of which the target is a member or with shareholders of a target S corporation) under section 338(h)(10) (i.e. 338(h)(10) election).

Alternatively, the seller and target can make a joint election, provided they satisfy the rules under section 336(e) (336(e) election). Similar to a section 338 election, the section 336(e) election treats a stock sale as a deemed asset sale for tax purposes, thereby providing the buyer a basis in the target’s assets equal to fair market value. Unlike the rules under section 338, however, the buyer does not have to be a corporation.

In certain circumstances involving a taxable stock sale between related parties, special rules (section 304) may re-characterize the sale as a redemption transaction in which a portion of the sale proceeds may be treated as a dividend to the seller. Whether the tax consequences of this recharacterization are adverse or beneficial depends on the facts. For example, if tax treaty benefits are not available, the dividend treatment may result in the imposition of US withholding tax (WHT) at a 30 percent rate on a portion of the sale proceeds paid by a US buyer to a foreign seller. On the other hand, the dividend treatment may be desirable on sales of foreign target stock by a US seller to a foreign buyer, both of which are controlled by a US parent corporation. In this case, with proper planning, a portion of the resulting deemed dividend from the foreign buyer and/or foreign target may be exempt from US federal income tax under the participation exemption implemented by the 2017 Tax Law as long as certain conditions are met.

Tax indemnities and warranties

In a stock acquisition, the target’s historical tax liabilities remain with the target. As such, it is important that the buyer procures representations and warranties from the seller (or its stockholders) in the stock purchase agreements to protect itself from risk of being exposed to any post-transaction liabilities (e.g. the 2017 Tax Law mandatory repatriation tax) arising from the target’s pre-transaction activities.

Where significant sums are at issue, the buyer generally performs a due diligence review of the target’s tax affairs. Generally, the buyer seeks tax indemnifications for a period through at least the expiration of the statute of limitations, including extensions. The indemnity clauses sometimes include a cap on the indemnifying party’s liability or specify a dollar amount that must be reached before indemnification occurs. Please note that KPMG LLP in the US cannot and does not provide legal advice. The purpose of this paragraph is to provide general information on tax indemnities and warranties that should be addressed and tailored by the client’s legal counsel to the client’s facts and circumstances.

Tax losses and other attributes

The 2017 Tax Law modifies the rules that govern the utilization of NOLs, and these rules were further modified by the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act), signed into law on 27 March 2020. In general:

1) NOLs arising in taxable years beginning on or before 31 December 2017 may be carried back 2 years and carried forward 20 years, and can offset up to 100 percent of a corporation’s taxable income.

2) NOLs arising in taxable years beginning after 31 December 2017 and before 1 January 2021 may be carried back 5 years and carried forward indefinitely, and can offset up to 100 percent of a corporation’s taxable income in taxable years beginning before 1 January 2021 (up to 80 percent of the corporation’s taxable income in taxable years beginning after 31 December 2020).

3) NOLs arising in taxable years beginning on or after 1 January 2021 can be carried forward indefinitely but cannot be carried back, and can offset up to 80 percent of a corporation’s taxable income.

As a result of differing carryback and carryforward rules and taxable income limitations, corporations (and potential acquirors) may need to track NOLs separately, based on their vintage.

Rules for utilization of capital losses remain unchanged under the 2017 Tax Law and CARES Act, which continues to allow corporations to carry capital loss back for 3 years and carry it forward for 5 years to the extent of available capital gains.

Section 382 imposes one of the most significant limitations on the utilization of a target’s NOLs (as well as capital losses and credits and disallowed business interest expense carryovers). Section 382 generally applies where a target that is a loss corporation undergoes an ‘ownership change.’ Generally, an ownership change occurs when more than 50 percent of the beneficial stock ownership of a loss corporation has changed hands over a prescribed period (generally 3 years).

The annual limitation on the amount of post-change taxable income that may be offset with pre-change NOLs (‘section 382 limitation’) is generally equal to the adjusted equity value of the loss corporation multiplied by a long-term tax-exempt rate established by the IRS. The adjusted equity value used in calculating the annual limitation is generally the equity value of the loss corporation immediately before the ownership change, subject to certain potential downward adjustments. Common adjustments include acquisition debt pushed down to the loss corporation and certain capital contributions to the loss corporation within the 2-year period prior to the ownership change.

If the aggregate fair market value of the target’s assets exceeds the target’s aggregate tax basis in its assets immediately prior to the ownership change (‘net unrealized built-in gain’ – NUBIG), and the target realizes some or all of its built-in gain during a 5-year recognition period following the ownership change (‘recognized built-in gain’ – RBIG), subject to certain limitations, the annual section 382 limitation can be increased by the amount of the RBIG. Currently, the excess of the target’s hypothetical depreciation and amortization based on fair market value allocable to depreciable and amortizable assets immediately prior to the ownership change over the target’s actual depreciation and amortization during the 5-year recognition period, can be treated as RBIG and can increase the annual limitation. However, newly proposed regulations under section 382(h) seek to eliminate the method that would allow for this result, with respect to ownership changes occurring 30 days after the release of the final regulations. (These proposed regulations are controversial and may be significantly modified prior to being published as final.)

On the contrary, if the fair market value of target assets is less than the tax basis immediately prior to the ownership change (’net unrealized built-in loss’ – NUBIL), any built-in loss realized during the 5-year recognition period following the ownership change (‘recognized built-in loss’ – RBIL), including any excess of actual depreciation and amortization over hypothetical depreciation and amortization based on fair market value allocable to depreciable and amortizable assets, can be subject to the section 382 annual limitation.

Similar to section 382, it is important to note that section 383 also seeks to restrict monetization of a loss corporation’s tax attributes by another profitable corporation, and section 384 seeks to restrict a loss corporation’s ability to utilize its pre-acquisition tax attributes against pre-acquisition built-in gain of an acquired profitable corporation.

In addition to changing the NOL rules, the 2017 Tax Law also repealed the US corporate alternative minimum tax (AMT) regime for tax years beginning after 2017. Excess AMT credits that have not yet been claimed are generally refundable. Under the CARES Act, a 50 percent refundable credit is allowed for 2018 with the remaining credit becoming fully refundable in 2019. Alternatively, corporate taxpayers may also elect to claim the entire refundable credit amount for 2018. As a practical matter, utilizing excess AMT credits and generating cash refunds as a result of such credits may be difficult for some taxpayers that face a section 383 limitation.

Consequences of a member of a consolidated group leaving such group

A corporation’s departure from a consolidated group is subject to the complex regulations that apply to US consolidated groups. Very generally, one consequence of a corporation’s departure from a consolidated group is the acceleration of any deferred items from transactions between the departing corporation and other members of the consolidated group. For example, gain on the sale of an item of property by one member of a consolidated group (S) to another consolidated group member (B) will generally be deferred under the consolidated return regulations until that property is transferred out of the consolidated group. If, however, either S or B leaves the consolidated group, S’s deferred gain will be accelerated and includible in taxable income (if S is the departing member, the deferred gain will be taken into account by S immediately before S leaves the consolidated group). There is an exception to this acceleration of deferred items for certain cases in which the entire consolidated group having the deferred items is acquired by another consolidated group.

Within a consolidated group, it is possible for a company (S) to have a negative tax basis in the shares of another company (B). This is referred to as an excess loss account and can arise as a result of debt leveraged distributions (e.g. B borrows in order to fund a dividend distribution) or debt leveraged generation of losses (e.g. B borrows and spends the proceeds on operating its business). Like the deferred intercompany items previously discussed, immediately before either B or S leaves the consolidated group, any excess loss account must be recognized as taxable income. There is an exception to this excess loss account recognition for certain cases in which the entire consolidated group having the excess loss account(s) is acquired by another consolidated group.

The departure of a corporation from a consolidated group raises numerous issues besides the acceleration of deferred items described above. For example, when a corporation ceases to be a member of a consolidated group during the tax year, the corporation’s tax year ends and consideration must be given to the allocation of income, gain, loss, deduction, credit, and potentially other attributes between the departing corporation and the consolidated group. The consolidated return regulations also contain complex rules that may reduce or eliminate loss realized (and/or certain tax attributes) on the departure of a consolidated group member. In addition, note that the departing corporation is potentially liable for the consolidated group’s entire tax liability for each year in which the departing corporation was a member of the consolidated group (even for a day), including the year in which the subsidiary leaves the consolidated group.

Pre-sale dividend

In certain circumstances, the seller may prefer to realize part of the value of its investment in the target through a pre-sale dividend. This may be attractive where the dividend is subject to tax at a rate that is lower than the tax rate on capital gains.

Generally, for corporations, dividends and capital gains are subject to tax at the same federal corporate tax rate of 21 percent. However, depending on the ownership interest in the subsidiary, a seller may be entitled to various amounts of dividend-received deduction (DRD) on dividends received from a US subsidiary if certain conditions are met. However, certain dividends may also result in reducing the tax basis of the target’s stock by the amount of the DRD.

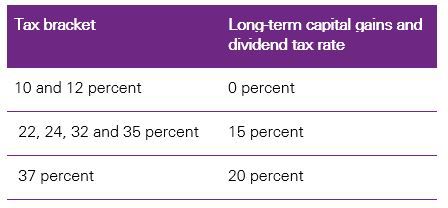

An individual is generally taxed on capital gains and dividends from domestic corporations and certain foreign corporations based on their marginal income tax bracket. See below for long-term capital gains rates for tax years beginning 2018. Qualified dividends are generally taxed at the general long-term capital gains rate.

Individuals are not entitled to DRDs on dividends. Thus, the tax effect of a pre-sale dividend may depend on the recipient‘s circumstances. Each case must be examined on its facts. In certain circumstances, proceeds of pre-sale redemptions of target stock may also be treated as a dividend by the recipient stockholder (see ‘Equity’ section).

Tax clearances

Generally, a clearance from the IRS is not required prior to engaging in an acquisition of stock or assets. A taxpayer can request a private letter ruling, which is a written determination issued to a taxpayer by the IRS national office in response to a written inquiry about the tax consequences of the contemplated transactions.

Although it provides a measure of certainty on the tax consequences, the ruling process can be protracted and time-consuming and may require substantial expenditures on professional fees. Thus, the benefits of a ruling request should be carefully considered beforehand.

Private letter rulings are taxpayer-specific and can only be relied on by the taxpayers to whom they are issued. Pursuant to section 6110(k)(3), such items cannot be used or cited as precedent. Nonetheless, such rulings can provide useful information about how the IRS may view certain issues.

Choice of acquisition vehicle

A particular type of entity may be better suited for a transaction because of its potential tax treatment. Previously, companies were subject to a generally cumbersome determination process to establish entity classification. However, the IRS and Treasury issued regulations that allow certain eligible entities to elect to be treated as a corporation or a partnership (where the entity has more than one owner) or as a corporation or disregarded entity (where the entity has only one owner). Rules governing the default classification of domestic entities are also provided under these regulations.

A similar approach is available for classifying eligible foreign business organizations, provided such entities are not included in a prescribed list of entities that are per se corporations (i.e. always treated as corporations).

Taxpayers are advised to consider their choice of entity carefully, particularly when changing the classification of an existing entity. For example, where an association that is taxable as a corporation elects to be classified as a partnership, the election is treated as a complete liquidation of the existing corporation and the formation of a new partnership. The election could thus constitute a material realization event that might entail substantial adverse immediate or future US tax consequences.

Local holding company

A US incorporated corporation is often used as a holding company and/or acquisition vehicle for the acquisition of a US target or a group of assets. Under the 2017 Tax Law, a corporation is subject to an entity-level federal corporate income tax rate of 21 percent, plus any applicable state and/or local taxes.

Despite the entity-level tax, a corporation may be a useful vehicle to achieve US tax consolidation to offset income with losses between the target group members and the buyer, subject to certain limitations (see ‘Group relief/consolidation’ section). Moreover, a corporation may be used to push down acquisition debt in certain circumstances, so that interest may offset the income from the underlying companies or assets. However, as noted earlier, a debt pushdown may limit the use of a target’s pre- acquisition losses under the section 382 regime (see ‘Tax losses and other attributes’ section).

Where a non-US person is a shareholder in a corporation, consideration should also be given to the Foreign Investment Real Property Tax Act (FIRPTA) (see next section).

Foreign parent company

Where a foreign corporation is directly engaged in business in the US through a US branch (or owns an interest in a fiscally transparent entity that conducts business in the US), it may be subject to net basis US taxation at the 21 percent corporate rate on income that is effectively connected to the US business (but only in the case of an entity entitled to benefits under a tax treaty, if that income is attributable to a US permanent establishment). The US also imposes additional tax at a 30 percent rate on branch profits deemed remitted overseas (subject to tax treaty rate reductions or exemptions). In addition, the foreign corporation will generally be subject to tax return filing obligations in the US.

Alternatively, a foreign corporation may be used as a vehicle to purchase US target stock, as foreign owners are generally not taxed on the corporate earnings of a US subsidiary corporation. However, dividends or interest from a US target remitted to a foreign corporation may be subject to US WHT at a 30 percent rate (which may be reduced under a tax treaty). Thus, careful consideration may be required where, for example, distributions from a US target are required to service debt of the foreign corporation (e.g. holding the US target through an intermediate holding company, as discussed later).

Generally, the foreign corporation’s sale of US target stock should not be subject to US taxation unless the US target was a US real property holding corporation (USRPHC) at any time during a specified measuring period. US target would be treated as USRPHC if the fair market value of the target’s US real property interests was at least 50 percent of the fair market value of its global real property interests plus certain other property used in its business during that specified measuring period. The specified measuring period generally is the shorter of the 5-year period preceding the sale or other disposition and the foreign corporation’s holding period for the stock.

A foreign seller of USRPHC stock may be subject to US income tax on the gain at standard corporate tax rates (generally 21 percent) and a 15 percent US WHT on the amount realized, including assumption of debt (the WHT is creditable against the tax on the gain). In addition, a sale of USRPHC stock gives rise to US tax return filing obligations.

Non-resident intermediate holding company

An acquisition of the stock of a US target may be structured through a holding company resident in a jurisdiction that has an income tax treaty with the US (an intermediate company) potentially to benefit from favorable US and foreign tax treaty WHT rates.

However, the benefits of the structure may be limited under anti-treaty shopping provisions found in most US treaties or under the US federal tax rules (e.g. Code, regulations).

Joint venture

Multiple buyers may use a joint venture vehicle to purchase a US target or US assets. A joint venture may be organized either as a corporation or a fiscally transparent entity (a flow-through venture), such as a partnership or LLC. A joint venture corporation may face issues similar to those described earlier (see ‘Local holding company’ section).

A flow-through venture generally is not subject to US income tax at the entity level (except in some states). Instead, its owners are taxed directly on their proportionate share of the flow-through venture’s earnings, whether or not distributed. Where the flow-through venture conducts business in the US, the foreign owners may be subject to net basis US taxation on their share of its earnings, as well as US WHT and US tax return filing obligations.

Choice of acquisition funding

Generally, a buyer (or an acquisition vehicle) finances the acquisition of a US target with its own cash, issuance of debt or equity, or a combination of these. The capital structure is critical due to the potential deductibility of debt interest. Certain 2017 Tax Law developments raise tax exposure concerns for a number of common US inbound acquisition financing structures (e.g. US inbound acquisition financing structures involving Luxembourg entities). The section 385 Regulations (see ‘Deductibility of interest’ section) also raise various considerations for US inbound acquisition financing.

Buyers of US target companies should carefully consider both 2017 Tax Law developments and recommendations from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to counter base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS), as well as the section 385 Regulations when deciding on what acquisition funding structure to use.

Debt

An issuer of debt may be able to deduct interest against its taxable income (see ‘Deductibility of interest’ section), whereas dividends on stock are non-deductible. Additionally, debt repayment may allow for tax-free repatriation of cash, whereas certain stock redemptions may be treated as dividends and taxed as ordinary income to the stockholder. Similar to dividends, interest may be subject to US WHT.

The debt placement and its collateral security should be carefully considered to help ensure that the debt resides in entities that are likely to be able to offset interest deductions against future profits. The debt should be adequately collateralized to help ensure that the debt will be respected as a genuine indebtedness. Moreover, the US debtor may recognize current income where the debt is secured by a pledge of stock or assets of controlled foreign companies (CFC). See ‘Foreign investments of a US target company’ section.

Deductibility of interest

Interest paid or accrued during a taxable year on a genuine indebtedness of the taxpayer generally is allowed as a tax deduction during that taxable year, subject to several exceptions, some of which are described below.

For interest to be deductible, the instrument (e.g. notes) must be treated for US tax purposes as debt and not as equity. The characterization of an instrument is largely based on facts, judicial principles and IRS guidance. Although a brief list of factors cannot be considered complete, some of the major considerations in the debt-equity characterization include:

- the intention of the parties to create a debtor-creditor relationship

- the debtor’s unconditional obligation to repay the outstanding amounts on a fixed maturity date

- the creditor’s rights to enforce payments

- the thinness of the debtor’s capital structure in relation to its total debt.

Shareholder loans generally should reflect arm’s length terms. Where a debtor has limited capability to service bank debt, its guarantor may be treated as the primary borrower. As a result, the interest accrued by the debtor may be re-characterized as a non-deductible dividend to the guarantor. This may entail additional US WHT consequences where the guarantor is a foreign person.

Interest deductions may be limited for certain types of acquisition indebtedness where interest paid or incurred by a corporation during the taxable year exceeds US$ million, subject to certain adjustments. However, this provision generally should not apply if the debt is not subordinated or convertible.

A US debtor’s ability to deduct interest on debt (whether extended or guaranteed by a related foreign person or third-party lender) may be further limited under the section 163(j) limitation on business interest. Except for the modifications discussed below resulting from changes made by the CARES Act, for taxable years beginning after 31 December 2017, the 2017 Tax Law substantially amended the earnings-stripping provision provided by section 163(j) (the section 163(j) limitation to generally disallow US tax deductions for the net business interest expense of any taxpayer in excess of 30 percent of a business’s ‘adjusted taxable income’). If certain conditions are met, the section 163(j) limitation can result in disallowance of interest expense deductions regardless of a taxpayer’s business form and whether the interest is owed to a related or third party.

For purposes of the section 163(j) limitation, business interest of a corporation includes any interest paid or accrued on indebtedness properly allocable to a trade or business. Under the 2017 Tax Law, disallowed business interest expense can be carried forward indefinitely to subsequent taxable years. However, future utilization of disallowed business interest expense carryforwards may be subject to limitation (including the section 382 limitation). Thus, during the tax due diligence phase, a buyer of a company that has a disallowed business interest expense carryforward should consider the extent to which section 382 imposes limitations on the utilization of this tax attribute.

The CARES Act temporarily modified the section 163(j) limitation under the 2017 Tax Law, increasing the limitation from 30 percent to 50 percent of ATI for tax years beginning in 2019 and 2020, for corporations. In addition, for tax years beginning in 2020, the CARES Act allows taxpayers to elect to use their ATI from their last tax year beginning in 2019 for their ATI in the 2020 tax year.

Depending on a US target’s facts, the section 163(j) limitation (and certain other 2017 Tax Law provisions — e.g. the hybrid mismatch rule) could result in increased taxable income for a US target. During the tax due diligence phase, it is important to evaluate a US target company’s US and global debt levels and to test the US target’s section 163(j) deductibility threshold. This analysis will help the foreign buyer determine potential US tax impact of existing debt levels, new debt and refinancings. This analysis will also help the foreign buyer evaluate the viability of alternative tax planning options for financing the acquisition of a US target company. Depending on the facts and circumstances, some planning opportunities to mitigate the impact of interest deduction limitations under revised section 163(j) may exist.

For testing purposes, the section 163(j) limitation is performed at the level of the tax filing entity. Regulations under the section 163(j) limitation generally provide that the limitation should be applied ‘after’ other interest disallowance, deferral, capitalization or other limitation provisions. Similar to NOLs, utilization of a US target’s disallowed interest expense carryforwards is subject to limitations following a change of control.

As a general matter, foreign companies with highly leveraged US operations should consider whether an excess interest situation currently exists or might exist in the foreseeable future. During the tax due diligence phase, a foreign buyer should consider undertaking this same inquiry for potential US target companies as well. If an excess interest situation does exist, it may make sense for the foreign company to explore ways to shift the debt burden from the US to an overseas affiliate that has sufficient debt capacity under local country rules. Also, other planning opportunities for further consideration may also exist. For example, by agreeing to a higher cost of goods sold (COGS) from suppliers in exchange for 90 days of trade credits (as opposed to borrowing in order to finance COGS on a real-time basis), it might be possible to convert interest expense that would otherwise be disallowed as a deduction under the section 163(j) limitation provision into a recoverable business expense. (Before undertaking any COGS planning, it is important to consider whether such planning could give rise to unanticipated US trade and customs costs).

Regulations under the final section 163(j) limitation confirm that a corporation can treat interest expense that had been deferred and carried forward under the legacy section 163(j) earnings-stripping provision as business interest paid or accrued in a tax year beginning after 2017 if it otherwise qualifies as business interest expense. These regulations also require that a CFC with business interest expense be subject to section 163(j) for the purpose of computing subpart F income (including GILTI) and income effectively connected with the conduct of a US trade or business.

In addition to the limitations discussed above, other limitations apply to interest on debt owed to foreign related parties and to certain types of discounted securities. For example, in October 2016, Treasury released regulations that seek to prevent companies from eroding the US tax base via deductible intercompany loans (the section 385 Regulations). As a general matter, the section 385 Regulations restrict the tax benefit of using intercompany debt in M&A transactions that involve foreign entity acquisitions of US target companies. Due to the nature of how the section 385 Regulations operate, these regulations can impact transaction structuring, tax due diligence and general tax planning.

Unless an exception applies, the general ‘Recast Rule’ of the section 385 Regulations can treat a debt instrument issued (or deemed reissued) by a US corporation to a related party after 4 April 2016, as equity if the debt instrument was issued:

- as a distribution of property

- to purchase related-party stock from a related-party seller

- in exchange for property from a related party in an asset reorganization.

The Recast Rule also provides a so-called funding rule that treats a debt instrument issued by a US corporation to a related party after 4 April 2016 as stock if it is issued for property (e.g. cash) and with a principal purpose of funding one of the transactions listed above. Under one subset of the funding rule, referred to as the ‘per se rule’, a debt instrument can be recast as equity if one or more of the following activities occur during the 36-month period before and after the loan issuance:

- making distributions in an aggregate amount that exceeds earnings and profits (E&P) earned in taxable years ending after 4 April 2016

- purchasing stock of a related party

- engaging in other transactions prohibited by the section 385 Regulations with a related party.

The Treasury has announced its intention to revise the Recast Rule to potentially replace the per se rule with a more streamlined and targeted set of rules that would apply to certain related-party debt instruments issued with a sufficient factual connection to a distribution or economically similar transaction. Treasury has requested comments from the public in this regard. However, no new rule has been proposed at this point, and any change is expected to be effective solely on a prospective basis.

The Treasury had also issued a series of documentation rules as part of the section 385 Regulations. These rules have been withdrawn.

Though the Recast Rules are primarily relevant to foreign-parented multinationals that own or acquire US corporations (or to buyers of such foreign- parented multinational groups), these rules can also apply to:

- debt between related US corporations that do not join together in filing a consolidated return

- members of a US-parented group that incur indebtedness, including pursuant to cash pooling arrangements, with foreign group members

- a US parent that incurs indebtedness to a foreign subsidiary (section 956 debt).

For debt issued before 4 April 2016, the section 385 Regulations do not apply, provided that the debt was not significantly modified or deemed reissued after 4 April 2016.

As a general matter, foreign parent entities (whether top-tier parents or intermediate parents) that have US subsidiaries should review their intercompany debt for section 385 compliance. To the extent that debt will be affected by the section 385 Regulations, the effective tax rate of the international group could be affected. For taxpayers to whom the Recast Rules apply — principally foreign multinationals — it is important that appropriate processes (i.e. internal tracking systems) be in place in order to track covered debt issuances and de-funding transactions, and to prevent unintended recasts. For potential acquisition targets, enhanced tax due diligence may be necessary to determine:

- whether the Recast Rules apply

- if the Recast Rules do apply, whether any debt is properly recast as equity under this rule

- the tax impact of any potential recast of debt as equity.

As a general matter, the following implications (among others) can arise if debt is recast as equity under the Recast Rules:

- disallowance of interest deductions

- US withholding tax consequences

- inability to treat cash repatriations from a US subsidiary to its foreign parent as a tax-free return of principal.

Withholding tax on debt and methods to reduce or eliminate it

The US imposes a 30 percent US WHT on interest payments to non-US lenders unless a statutory exception or favorable US treaty rate applies. Further, structures that interpose corporate lenders in more favorable tax treaty jurisdictions may not benefit from a reduced WHT because of the conduit financing regulations of section 1.881-3 and anti-treaty-shopping provisions in most US treaties. (See ‘Non-resident intermediate holding company’ section.)

No US WHT is imposed on portfolio interest. Portfolio interest constitutes interest on debt held by a foreign person that is not a bank and owns less than 10 percent (by vote) of the US debtor (including options, convertible debt, etc., on an as-converted basis).

Generally, no US WHT is imposed on interest accruals until the US debtor pays the interest or the foreign person sells the debt instrument. Thus, US WHT on interest may be deferred on zero coupon bonds or debt issued at a discount, subject to certain limitations discussed below (see ‘Discounted securities’ section).

Considerations for debt funding

Some of the important factors to consider:

- Debt should be borne by US debtors that are likely to have adequate positive cash flows to service the debt principal and interest payments.

- Debt should satisfy the various factors of indebtedness to avoid being reclassified as equity.

- Debt must be adequately collateralized to be treated as genuine indebtedness of the issuer.

- The interest expense must qualify as deductible under the various rules limiting interest deductions discussed earlier.

- Debt between related parties must be issued under terms that are consistent with arm’s length standards.

- Guarantees or pledges on the debt may trigger the current inclusion of income under the subpart F rules.

Equity

The acquisition of a US target may be financed by issuing common or preferred equity. Distributions may be classified as dividends where paid out of the US target’s current or accumulated E&P (similar to retained earnings). Distributions in excess of E&P are treated as the tax-free recovery of tax basis in the stock (determined on a share-by-share basis). Distributions exceeding both E&P and stock basis are treated as capital gains to the holder.

US issuers of stock interests generally are not entitled to any deductions for dividends paid or accrued on the stock. Generally, US individual stockholders are subject to tax on dividends from a US target based on their relevant income tax bracket (see ‘Pre-sale dividend’ section for the applicable tax rates). Stockholders who are US corporations are subject to tax at the 21 percent rate applicable to corporations, but they are entitled to DRDs when received from US corporations depending on their ownership interest (see ‘Pre-sale dividend’ section).

Generally, dividends paid to a foreign shareholder are subject to US WHT at 30 percent unless eligible for favorable WHT rates under a US treaty. The WHT rules provide limited relief for US issuers that have no current or accumulated E&P at the time of the distribution and anticipate none during the tax year. Such a US issuer may elect out of the WHT obligation where, based on reasonable estimates, the distributions are not paid out of E&P.

Generally, no dividend should arise unless the issuer of the stock declares a dividend or the parties are required currently to accrue the redemption premium on the stock under certain circumstances. Of course, US WHT is also imposed on US-source constructive (i.e. deemed paid) dividends. For example, where a subsidiary sells an asset to its parent below the asset’s fair market value, the excess of the fair market value over the price paid by the parent could be treated as a constructive dividend.

Generally, gains from stock sales (including redemptions) are treated as capital gains and are not subject to US WHT (but see the discussion of FIRPTA in the ‘Foreign parent company’ section).

Certain stock redemptions may be treated as giving rise to distributions (potentially treated as dividends) where the stockholder still holds a significant amount of stock in the corporation post-redemption of either the same class or another class(es). Accordingly, the redemption may result in ordinary income for the holder that is subject to US WHT. See this report’s sections on ‘Purchase of assets’ and ‘Purchase of shares’ for discussion of certain tax-free reorganizations.

Hybrid instruments and entities

Instruments (or transactions) may be treated as indebtedness (or a financing transaction) of the US issuer, while receiving equity treatment under the local (foreign) laws of the counterparty. This differing treatment may result in an interest deduction for the US party while the foreign party benefits from the participation exemption or FTCs that reduce its taxes under local law. Alternatively, an instrument could be treated as equity for US tax purposes and as debt for foreign tax purposes.

Similarly, an entity may be treated as a corporation for US tax purposes and a transparent entity for foreign tax purposes (or vice versa).

Under certain circumstances, this differing treatment can give rise to ‘stateless income’ (income that is taxed nowhere).

Certain provisions of the 2017 Tax Law seek to discourage use of hybrid entities and instruments that give rise to stateless income. Specifically, the 2017 Tax Law contains a ‘hybrid mismatch rule’ that generally disallows deductions for related-party interest or royalties paid or accrued in connection with certain hybrid transactions or by, or to, hybrid entities if (i) the related party does not have a corresponding income inclusion under local tax law, or (ii) such related party is allowed a deduction with respect to the payment under local tax law. This provision, which incorporates the concepts of the OECD BEPS Action 2, generally applies to tax years beginning after 31 December 2017, but with a 1-year delay for purposes of the ‘imported mismatch’ rules.

For purposes of this hybrid mismatch rule, a hybrid transaction includes any transaction or instrument under which one or more payments are treated as interest or royalties for US federal income tax purposes but are not treated as such under the local tax law of the recipient. A hybrid entity is one that is treated as fiscally transparent for US federal income tax purposes (e.g. a disregarded entity or partnership) but not for purposes of the foreign country of which the entity is resident or is subject to tax (hybrid entity), or an entity that is treated as fiscally transparent for foreign tax law purposes but not for US federal income tax purposes (reverse hybrid entity). Treasury issued regulations under the hybrid mismatch rule, which would broaden the reach of the hybrid mismatch rule to encompass reverse hybrids and branch payments and, at the same time, requires a link between hybridity and the deduction/non-inclusion outcome. The regulations also apply the hybrid mismatch concept to ‘imported mismatches’ where the US taxpayer makes a non-hybrid deductible payment to a foreign affiliate that is connected to a hybrid mismatch between the foreign payee and some other foreign party. Finally, the regulations implementing the hybrid mismatch rule also modified the ‘check-the-box’ regulations for US domestic reverse hybrids to treat such entities as having consented to be treated as dual resident corporations under the dual consolidated loss rules (further details in ‘Dual residency’ section below), thereby addressing a long-standing gap in those rules.

In practical terms, the hybrid mismatch rule eliminates the US tax benefits of some hybrid structures that foreign multinationals have commonly used in the past to finance US operations. Foreign multinationals should consider revisiting their US inbound financing structures in view of the new rule and also consider this rule when determining the acquisition funding structure for US target companies.

Buyers of US target companies should also carefully consider the OECD BEPS recommendations concerning hybrids during the tax due diligence phase and before implementing any structures concerning acquisition finance planning and/or acquisition integration planning. Where hybrid instruments and entities are concerned, many jurisdictions have already implemented some of the OECD’s BEPS recommendations (and at the EU level, under the ATAD 1 and ATAD 2 initiatives) that undo some of the tax benefits of hybrid structures commonly implemented by US multinationals. It is important to keep this in mind when acquiring a US multinational that has significant operations in such jurisdictions.

In addition to the new hybrid mismatch rule, the 2017 Tax Law also precludes CFC hybrid dividends from qualifying for the DRD. The 2017 Tax Law broadly defines the term ‘hybrid dividend’ to mean a payment for which a CFC receives a deduction or other tax benefit in a foreign country. The 2017 Tax Law generally treats hybrid dividends between tiered CFCs as subpart F income. Despite this subpart F income treatment, the 2017 Tax Law does not allow utilization of FTCs resulting from hybrid dividends. Under the issued regulations, US shareholders are required to maintain a hybrid deduction account to track foreign deductions (arising after 2017) with respect to the CFC’s hybrid equity, and the CFC’s otherwise DRD-eligible earnings are rendered ineligible by an amount corresponding to the foreign deductions. The hybrid deduction account is a tax attribute associated with the CFC stock that can be succeeded to by acquirers of the CFC stock in certain transactions.

Discounted securities

A US issuer may issue debt instruments at a discount to increase the demand for its debt instruments. The issuer and the holder are required currently to accrue deductions and income for the original issue discount (OID) accruing over the term. However, a US issuer may not deduct OID on a debt instrument held by a related foreign person unless the issuer actually paid the OID.

A corporate issuer’s deduction for the accrued OID may be limited (or even disallowed) where the debt instrument is treated as an applicable high yield discount obligation (AHYDO). In that case, the deduction is permanently disallowed for some or all of the OID if the yield on the instrument exceeds the applicable federal rate (for the month of issuance) plus 600 basis points. Any remaining OID is only deductible when paid.

Deferred settlement

In certain acquisitions, the parties may agree that the payment of a part of the purchase price should be made conditional on the target meeting pre-established financial performance goals after the closing (earn-out). Where the goals are not met, the buyer can be relieved of some or all of its payment obligations. An earn-out may be treated as either the payment of the contingent purchase price or ordinary employee compensation (where the seller is also an employee of the business). Buyers generally prefer to treat the earn-out as compensation for services, so they can deduct such payments from income.

In an asset acquisition, the buyer may capitalize the earn-out payment into the assets acquired but only in the year such earn-out amounts are actually paid. Such capitalized earn-out amounts should be depreciated/amortized over the remaining depreciable/amortizable life of the applicable assets. In a stock acquisition, the earn-out generally adds to the buyer’s basis in the target stock. Interest may be imputed on deferred earn-out payments unless the agreement specifically provides for interest.

Other considerations

Documentation

Documentation of each step in the transaction and the potential tax consequences is recommended. Taxpayers generally are bound by the form they choose for a transaction, which may have material tax consequences. However, the government may challenge the characterization of a transaction on the basis that it does not reflect its substance. Thus, once parties have agreed on the form of a transaction, they are well advised to document the intent, including the applicable Code sections. Parties should also maintain documentation of negotiations and appraisals for purposes of allocating the purchase price among assets.

Contemporaneous documentation of the nature of transaction costs should also be obtained.

Although the parties to a transaction generally cannot dictate the tax results through the contract, documentation of the parties’ intent can be helpful should the IRS challenge the characterization of the transaction.

Concerns of the seller

Generally, the seller’s tax position influences the structure of the transaction. The seller may prefer to receive a portion of the value of the target in the form of a pre-sale dividend for ordinary income treatment or to take advantage of DRDs. A sale of target stock generally results in a capital gain, except in certain related-party transactions (see ‘Purchase of shares’ section) or on certain sales of shares of a CFC. In addition, a foreign seller of a USRPHC may be subject to tax and withholding based on FIRPTA, as discussed in the ‘Foreign parent company’ section.

A sale of assets could also result in capital gains treatment except for depreciation recapture, which may have ordinary income treatment. Where the seller has no tax attributes to absorb the gain from asset sales, gains may be deferred where the transaction qualifies as a like-kind exchange, in which the seller exchanges property for like-kind replacement property (e.g. exchange of real estate). As previously mentioned, it seems likely that the seller of a US target company may be more willing to sell assets than before due to the US corporate tax rate reduction and 100 percent expensing for qualifying purchases of depreciable tangible property. Under the 2017 Tax Law, a C corporation that sells an asset and reinvests the proceeds into qualifying depreciable tangible property receives a cash tax benefit due to acceleration of deductions.

Alternatively, the transaction may be structured as a tax-free separation of two or more existing active trades or businesses formerly operated, directly or indirectly, by a single corporation for the preceding 5 years (spin-off). Stringent requirements must be satisfied for the separation to be treated as a tax-free spin-off.

Company accounting[2]

This discussion is a high-level summary of certain accounting considerations associated with business combinations and non-controlling interests.

Accounting Standards Codification (ASC) Topic 805, Business Combinations (ASC 805) and ASC Subtopic 810-10, Consolidations — Overall (ASC 810-10) require most identifiable assets acquired, liabilities assumed and non-controlling interest in the acquiree to be recorded at ‘fair value’ in a business combination and require non-controlling interests to be reported as a component of equity.

ASC 805-10-20 defines a ‘business combination’ as a transaction or other event in which an entity (the acquirer) obtains control of one or more businesses (the acquiree or acquirees). A business combination may occur even where control is not obtained by purchasing equity interests or net assets, as in the case of control obtained by contract alone. This can occur, for example, when a minority shareholder’s substantive participating rights expire and the investor holding the majority voting interest gains control of the investee.

ASC 805-10-55-3A defines a business as an integrated set of activities and assets that is capable of being conducted and managed to provide a return in the form of dividends, lower costs, or other economic benefit directly to investors or other owners, members or participants.

Under ASC 805-10-55-5, an integrated set of activities and assets (set) is a business if it has, at a minimum, an input and a substantive process that together significantly contribute to the ability to create outputs. ASC 805-10-55-5A also has an initial screening test that reduces the population of transactions that an entity needs to analyze to determine whether there is an input and a substantive process in the set.

Business combinations are accounted for by applying the acquisition method. Companies applying this method:

- identify the acquirer

- determine the acquisition date and acquisition-date fair value of the consideration transferred, including contingent consideration

- recognize, at their acquisition-date fair values (with limited exceptions), the identifiable assets acquired, liabilities assumed and any non-controlling interests in the acquiree

- recognize goodwill or, in the case of a bargain purchase, a gain.

ASC 805 allows for a measurement period for the acquirer to obtain the information necessary to enable it to complete the accounting for a business combination. Until necessary information can be obtained, and for no longer than 1 year after the acquisition date, the acquirer reports provisional amounts for the assets, liabilities, equity interests or items of consideration for which the accounting is incomplete.

A company that obtains control but acquires less than 100 percent of an acquiree records 100 percent of the acquiree’s assets (including goodwill), liabilities and non-controlling interests, measured at fair value with few exceptions, at the acquisition date.

ASC 810-10 specifies that non-controlling interests are treated as a separate component of equity, not as a liability or other item outside of equity. Because non-controlling interests are an element of equity, increases and decreases in the parent’s ownership interest that leave control intact are accounted for as equity transactions (i.e. as increases or decreases in ownership) rather than as step acquisitions or dilution gains or losses.

When there is a change in the parent’s ownership interest but control is retained, the carrying amount of the non-controlling interests is adjusted to reflect the change in ownership interests. Any difference between (i) the fair value of the consideration received or paid and (ii) the amount by which the non-controlling interest is adjusted is recognized directly in equity attributable to the parent (i.e. additional paid-in capital).

A transaction that results in the loss of control generates a gain or loss comprising a realized portion related to the portion sold and an unrealized portion on the retained non-controlling interest, if any, that is re-measured to fair value. Similarly, a transaction that results in obtaining control could result in a gain or loss on previously held equity interests in the investee since the acquirer would account for the transaction by applying the acquisition method on that date.

Group relief/consolidation

Affiliated US corporations may elect to file consolidated federal income tax returns as members of a consolidated group.

Generally, an affiliated group consists of chains of 80 percent-owned (by vote and value) corporate subsidiaries (members) having a common parent that owns such chains directly or indirectly.

The profits of one member may be offset against the current losses of another member. In most cases, gains or losses from transactions between members are deferred until the participants cease to be members of the consolidated group or otherwise cease to exist. Complex rules may limit the use of losses arising from the sale of stock of a member to unrelated third parties (i.e. unified loss rules).

Transfer pricing

Following an acquisition of a target, all transactions between the buyer and the target must be consistent with arm’s length standards. If related parties fail to conduct transactions at arm’s length, the IRS may reallocate gross income, credits, deductions or allowances between the participants to prevent tax avoidance or to reflect income arising from such transactions. Such transactions may include loans, sales of goods, leases or licenses. Contemporaneous documentation must be maintained to support intercompany transfer pricing policies.

Net investment income tax

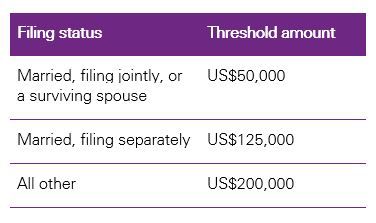

Section 1411 imposes a 3.8 percent tax on net investment income (NII) of individuals, estates and trusts with gross income above a specified threshold. The NII tax does not apply to S corporations and partnerships (but may apply to their owners), C corporations, non-resident aliens, foreign trusts and estates, grantor trusts, tax-exempt trusts (e.g. charitable trusts), and certain other types of trusts and funds (e.g. REITs, electing Alaska native settlement trusts, and common trust funds).

In the case of an individual, the NII tax is applied to the lesser of the NII or the modified adjusted gross income in excess of the threshold amounts as follows:

Source: Code section 1411(b)

NII includes three major categories of income:

- income from passive trades or businesses and from the business of trading financial instruments and commodities

- interest, dividend, annuities, royalties and rents (unless derived in the ordinary course of a trade or business not listed in category 1 above)

- net gains from the disposition of property other than property held in a trade or business not listed in category 1 above.

The 2017 Tax Law left the 3.8 percent NII tax in place.

Dual residency

Generally, the NOLs of a dual resident corporation (DRC) and a net loss attributable to a separate unit cannot be used to offset the taxable income of a US affiliate or the domestic corporation that owns the separate unit. Any such loss is a dual consolidated loss (DCL) subject to Treasury regulations under section 1.1503(d)-1 through 8.