Few modern international companies have static business models. Most businesses continually adjust them — whether by adopting digital processes or via acquisition and growth — to deliver competitive advantage. This puts pressure on tax teams to stay on top of developments and adapt the company’s tax strategy as operations shift in an equally dynamic international tax environment.

In this article, we explore these challenges in detail with a close look at how tax teams can manage disruptive business model change in the global automotive industry.

All businesses are becoming digital businesses

In an era when technology is disrupting business practices and opening opportunities like never before, business model change that embeds digitalization across markets, functions and processes is top of mind for CEOs in every industry.

In a recent survey, more than half of companies in all industries globally say they have a digital strategy that is enterprise-wide or specific to individual business units. About one-third of companies that don’t have one now say they’re working on one1.

As global companies tweak their business models or reinvent themselves entirely, many heads of tax strive to keep up, but the evolving international tax reality sets a number of hurdles for them to clear. Top challenges for today’s tax teams include:

- traditional local tax systems that do not fit evolving digital business models, creating tax risk and uncertainty

- fast-moving tax legislation discussions toward a common global tax base being led at the international level by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

- increasing emphasis on tax compliance and responsibility amid heightened scrutiny from tax authorities, media and the public, producing both financial and reputational risk

- the need to surmount the first three challenges while optimizing the company’s tax position and how the tax function is organized.

Things get even more complicated for tax teams as digital business models blur the lines between traditional industries and alter the nature of transactions.

Case study: new business models and tax strategies for automotive companies

Consider the automotive industry, which is in the midst of huge disruption. Today, global- technology giants are working to design and make new smart car brands, and other tech companies such as ride-sharing applications are also seeking a share of the market.

Traditional large original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) are defending their turf and competing against the new breed of competitors by branching out from physical goods to software and services. To do this, they need to adopt business models that differ dramatically from those of OEMs of the past.

Their core business is currently still selling hardware — the car — but all OEMs are gearing up to deliver a range of digital services as well in order to become more and more a service provider with direct interaction with customers. Like our phones and watches, cars are becoming platforms for downloading software-as-a-service. Along with navigation, music and messaging apps on your dashboard, you can download a range of driver-specific apps. Some of these can help you find and pay for nearby parking spaces, for example. Others can park your car for you. They all have in common that they focus on the individual personal needs of the customer in order to generate an additional value in the customer’s lifestyle. The phones, watches and cars should become an indispensable part of the user’s life.

A second trend gives drivers the ability to subscribe to digital services for their cars for time-limited periods. Known as “function on demand”, these services allow you to switch your car’s functions on and off so you pay for them only when you want them. On a long drive, you can soon activate a one-time chair massage. For two or three months in winter, you’ll be able to sign up to have your car heat your seats and steering wheel.

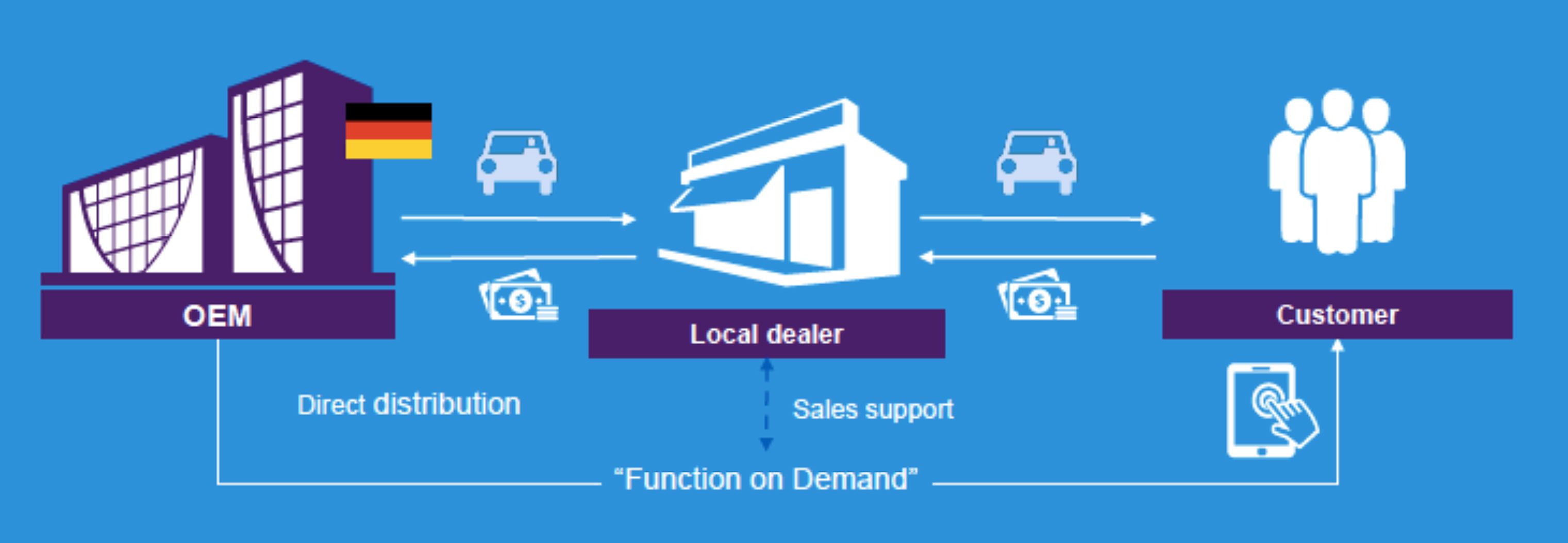

Traditional OEM business models can’t deliver the new mix of product and services. Moving to new business models, however, can stir up host of new tax problems. In the past, OEMs would ship goods to distributors, such as local dealers or importers under an agency arrangement, who would in turn sell them to end consumers. But with function on demand, the OEM is switching from business-to-business (B2B) transactions and selling digital services across borders to consumers directly.

Function on demand: new business model

For the OEM, the tax issues and solutions that come with a change to a business-to-consumer (B2C) model can vary greatly among the jurisdictions the digital services are sold or licensed to.

For example:

- Permanent establishment (PE) issues: New income tax payment and compliance obligations can arise if the OEM’s local sales support activities create an agency PE. This could create challenges in determining how to allocate profits to the PE, or trigger automatic value added tax implications. Tax teams need to understand and meet these obligations location by location at a time when local and international PE definitions are in flux.

- Withholding tax (WHT) issues: Fees for connected services might attract withholding tax, depending on the local rules and tax treaties at play where the consumer is located. Some jurisdictions count on WHT to capture new types of digital activity within their existing traditional tax regimes. Whether and how much WHT is payable can depend on whether the payment is considered as license or service fee under local law or the terms of relevant tax treaty. Divergent and often vague definitions of “license” can make this hard to determine.

WHT rules for B2B and B2C transactions can also differ. In fact, as we discuss below, for some OEMs, the new set of WHT rules that kick in when they start selling B2C can be a showstopper for the business model. Especially, if private customers are required to fulfill specific compliance obligations or even withhold taxes.

- Transfer pricing issues: It’s becoming even more likely that international transfer pricing rules will change significantly in the coming years. The OECD is consulting on revisions to longstanding rules for nexus and allocating profit as part of its digital economy work stream. This has the potential to affect a wide range of companies. It may also fundamentally alter how the arm’s length principle is applied, and how profits and intangible property are allocated.

- Evolving tax initiatives solely focused on digital business models: Several unilateral measures which mainly targeting digital businesses are already implemented or are even about to enter into force soon. New nexus approaches linked to a “significant economic presence” or “digital service taxes” on generated revenues may also create additional tax risks need to be considered when rolling out digital services in respective markets.

The biggest challenge for the OEM’s tax team lies in gaining a global view of the tax costs and consequences in each jurisdiction that the new features will be offered in. This task is harder than usual since most jurisdictions do not address such transactions directly in either domestic law or their tax treaties.

Gaining tax certainty before new business roll-out

A common strategy available in many jurisdictions is for the company to apply for a tax ruling in advance to gain certainty on the tax effects of business model changes, such as whether a permanent establishment will be created and whether function-on-demand payments are licenses or royalties for tax treaty purposes.

Companies taking this route should delay launching the new business there until the rulings have been granted in all relevant jurisdictions. Otherwise, an unfavorable ruling could jeopardize the success of the new activities.

For example, different tax treaties may set different compliance obligations for B2B and B2C transactions in order to secure WHT exemptions. If a tax authority rules that B2C obligations should apply, the company’s consumers would need to meet compliance obligations to eliminate WHT on their payments. From a business point-of-view, this would be clearly unacceptable, so the company would need to develop an alternative way of doing business than first proposed. This could be costlier, more difficult and even brand-damaging if the business models changes are already in operation.

By requesting rulings and taking other steps to determine the business model’s tax effects, the tax team can devise and put in place the optimal solution for each jurisdiction while opening visibility over the company’s tax compliance globally.

Rather than having tax teams race to catch up with the tax effects of business model changes, a better approach sees tax teams brought to the table early, when the model is being developed. This way, the new model can be designed in ways that meet your company’s business objectives while avoiding negative tax impacts and gaining more certainty on PE, withholding tax, transfer pricing and other issues.

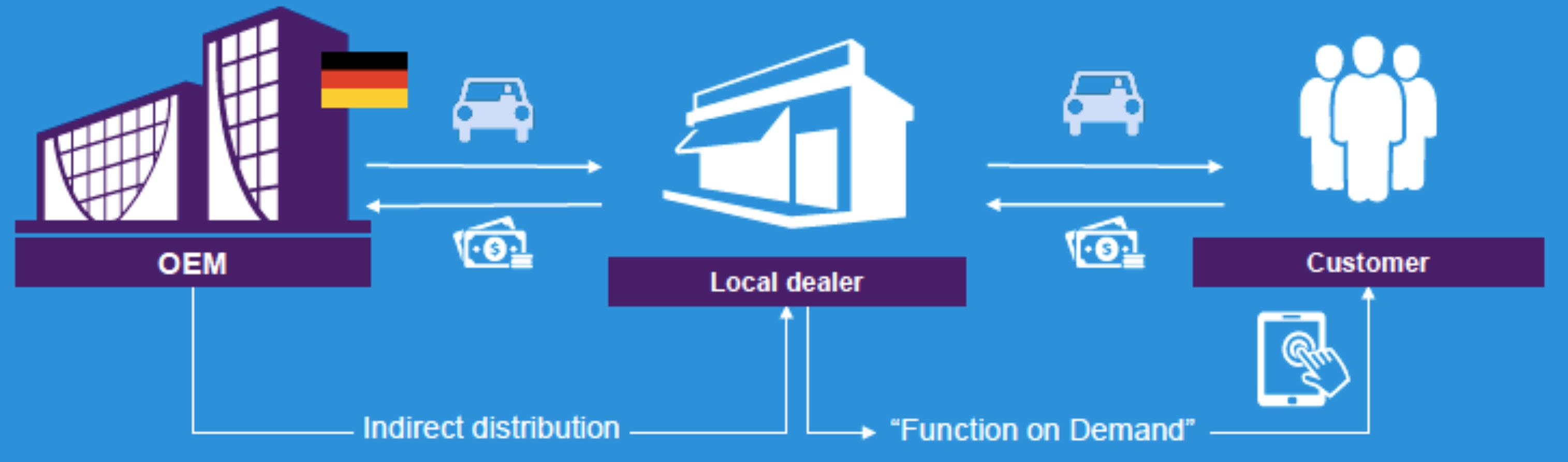

For software-as-a-service and functions on demand offered by OEMs, for example, many tax issues and uncertainties can be resolved by adopting an alternative business model. In our example, the OEM could do this by setting up an agency arrangement that allows local dealers to contract with consumers for the OEM’s digital services.

Function on demand: alternative new business model

These strategies may be out of step with broader business objectives, however, if the OEM wants to hold its intangible property (IP) centrally and keep control over its rights to the data derived from the IP, as well as getting in direct contact with its final customers.

Whatever business model and tax strategy the company ultimately adopts, the tax team needs to monitor them continually and get set for the next disruption as technology, market forces and international tax continue to spur change.

How current tax rules will evolve is uncertain. Significant change seems inevitable as many countries, like the U.S. and Canada, await the outcome of the OECD’s digital taxation project, while others, like the U.K. and France, move ahead with homegrown, unilateral measures.

Takeaways for tax leaders

Against the backdrop of shifting business models and changing tax rules, heads of tax can help ensure their tax strategy sets the stage for success by:

- getting involved early in business planning processes to make sure tax matters are front and center as new models are designed

- encouraging the business to hold the launch of new business models until any uncertainty over tax matters is resolved in all relevant jurisdictions (e.g. via rulings, negotiations with tax authorities)

- embedding a tax team member in the company’s strategy and business development unit

- assigning a digital tax manager to coordinate multidisciplinary tax matters (e.g. corporate income tax, transfer pricing and VAT)

- observing or taking part in international tax policy debates to keep up with and prepare for developments as they unfold

Contributors

Dr. Andreas Ball

Partner, Tax

KPMG in Germany

Nathalie Cordier-Deltour

Partner, Tax,

KPMG Avocat in France

James Magrath

Partner, Tax

KPMG in the UK

Footnote

1Harvey Nash / KPMG – CIO Survey 2018

Episode 16

Transcript (PDF 295 KB).

Connect with us

- Find office locations kpmg.findOfficeLocations

- kpmg.emailUs

- Social media @ KPMG kpmg.socialMedia